Modafinil

Modafinil, sold under the brand name Provigil among others, is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant and eugeroic (wakefulness promoter) medication used primarily to treat narcolepsy,[3][8][15] a sleep disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden sleep attacks.[16] Modafinil is also approved for stimulating wakefulness in people with sleep apnea and shift work sleep disorder.[3] It is taken by mouth.[3][8] Modafinil is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in people under 17 years old.[8]

Common side effects of Modafinil include anxiety, insomnia, dizziness, and headache. Modafinil has potential for causing severe allergic reactions, psychiatric effects,[3] hypersensitivity, adverse interactions with prescription drugs, and misuse or abuse.[3][8][15] Modafinil may harm the fetus if taken during or two months prior to pregnancy.[17]

While modafinil is used as a cognitive enhancer, or "smart drug," among healthy individuals seeking improved focus and productivity,[18][19] its use outside medical supervision raises concerns regarding potential misuse or abuse.[3][8][20] Research on the cognitive enhancement effects of modafinil in non-sleep deprived individuals has yielded mixed results, with some studies suggesting modest improvements in attention and executive functions, while others show no significant benefits or even a decline in cognitive functions at high doses.[21][22]

Uses

[edit]Medical

[edit]Sleep disorders

[edit]Modafinil, a eugeroic or wakefulness-promoting drug, is primarily used for treating narcolepsy, a sleep disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden sleep attacks.[16] Being a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant itself,[23] modafinil has lower addictive potential than classical stimulants such as amphetamine, cocaine, or methylphenidate,[13][24][25] but still produces psychoactive and subjective effects typical of classical stimulants.[3][8][20]

Narcolepsy causes a strong urge to sleep during the day and can include symptoms like cataplexy (sudden muscle weakness), sleep paralysis (inability to move or speak while falling asleep or waking up), and hallucinations. Narcolepsy is linked to a lack of the brain chemical hypocretin (orexin), primarily produced in the hypothalamus.[26][27] Modafinil is not a cure for narcolepsy, but it can help manage the symptoms. While modafinil is primarily used to treat excessive sleepiness, it may also help reduce the frequency and severity of cataplexy attacks in some people. Modafinil is approved for management of narcolepsy with or without cataplexy. However, it is not specifically approved for the treatment of cataplexy.[28][29]

Modafinil is also prescribed for shift work sleep disorder.[8]

Modafinil performs moderately (but better than armodafinil or solriamfetol)[30] as a drug to overcome excessive daytime sleepiness caused by obstructive sleep apnea,[31] though it is recommended that people with apnea use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, that is a sleep breathing apparatus to prevent apnea, before starting modafinil.[8][22][32] When obstructive sleep apnea is comorbid with narcolepsy, modafinil is an effective drug to reduce the associated excessive daytime sleepiness.[33]

Modafinil's use varies by region. In the US, it is approved for adult narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder, and obstructive sleep apnea, but not for children.[20] In the UK and the EU, since 2014, it is approved solely for narcolepsy, including in children (pediatric narcolepsy), with its use for other conditions restricted by the European Medicines Agency.[28][34]

As of 2024,[update] both the French and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine strongly recommend modafinil as the first-choice treatment for narcolepsy.[35] In Europe, modafinil is considered one of the primary drugs recommended for treating narcolepsy according to the guidelines.[36]

Multiple sclerosis-related fatigue

[edit]The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, along with various non-governmental organizations focused on multiple sclerosis (MS), endorse the off-label use of modafinil to alleviate fatigue associated with MS.[20][37][38]

MS-related fatigue is a common and often debilitating symptom experienced by people with multiple sclerosis.[39][40][41][42] It can significantly impact their daily functioning, quality of life, and ability to perform everyday activities. When prescribed for MS-related fatigue management, modafinil works by promoting wakefulness and increasing alertness without causing drowsiness or disrupting nighttime sleep. People with multiple sclerosis often report increased energy levels, reduced feelings of tiredness, improved cognitive function, and an overall improvement in their quality of life when taking modafinil.[43] While modafinil can provide relief from MS-related fatigue symptoms,[43] it does not treat the underlying cause or cure MS itself. The primary goal of using modafinil in MS is symptom management and improving daily functioning.[41][42][44][45] The effects of modafinil on other aspects of MS-related fatigue, such as severity and cognitive function, are less clear.[45][43]

While modafinil has been shown to be effective in managing fatigue in people with MS,[43][41] optimal dosing and treatment schedules are not well established.[41][42][44][45]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

[edit]Modafinil is occasionally prescribed off-label for individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[46][47][48] It has not consistently shown efficacy in treating adult ADHD,[49] especially when compared to other treatments such as lisdexamfetamine.[50][51] In children, modafinil is efficient in treating ADHD symptoms.[52][53]

Given its approved status in the US to treat narcolepsy, physicians can also prescribe modafinil for off-label uses, such as treating ADHD in both children and adults.[54][55][56]

The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) suggests modafinil as a second-line choice for ADHD, after the first-line choices such as bupropion are exhausted.[57]

Bipolar disorder

[edit]Modafinil is used off-label as an adjunctive treatment (i.e., in combination therapy) for the acute depressive phase in bipolar disorder.[58][59][60][61] The depressive phase of bipolar disorder may feature excessive sleepiness and fatigue. Adjunctive treatment with modafinil can be used as an augmentation for the main treatment to increase its effect and is safe and effective, especially for people who do not respond well to standard antidepressants.[62][63][49] Modafinil does not significantly increase the risk of mood switch to mania or suicide attempts in people with bipolar disorder.[64][62] Modafinil may also have cognitive benefits in people with bipolar disorder who are in a remission state.[65][66][49]

Whereas modafinil and armodafinil are approved for narcolepsy, they have been repurposed as adjunctive treatments to alleviate symptoms of acute depressive phase in people with bipolar disorder.[67] Drug repurposing in psychiatry is a strategy for discovering new uses for drugs that have already been approved or tested in clinical trials for other illnesses. As such, drug repurposing is a rapid, cost-effective, and reduced-risk strategy for the development of new treatment options for psychiatric disorders.[67] 2021 meta-analysis concluded that add-on modafinil and armodafinil were more effective than placebo on response to treatment, clinical remission, and reduction in depressive symptoms, with only minor side effects, but the effect sizes are small and the quality of evidence is therefore low, limiting the clinical relevance of the evidence.[67][68] Very low rates of mood swing (a change in mood from one extreme to another)[64][69] have been observed with modafinil and armodafinil in depressive phase of bipolar disorder.[60][70]

Occupational

[edit]Modafinil was used by the French Foreign Legion,[71] US Air Force,[72][73] and US Marine[74] infantry during the Gulf War to enhance "operational tempo" (a term that denotes the speed and intensity at which military operations or activities are executed), aiming to optimize the overall performance and efficiency of the unit.[73][75][76]

Armed forces in various countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, India, and France, have considered modafinil as an alternative to traditional amphetamines for managing sleep deprivation in combat or extended missions.[77] The US military approved modafinil for specific Air Force missions, replacing amphetamines for fatigue management.[78] The use of modafinil in military contexts without sleep deprivation is not recommended due to inconclusive evidence on its cognitive enhancement benefits and potential risks of adverse effects.[72]

Modafinil is also available to astronauts aboard the International Space Station for the management of fatigue caused by circadian dyssynchrony in orbit.[79]

Non-medical

[edit]Modafinil has been used non-medically as a "smart drug"[18][19] by various groups, including students,[80][81][82] office workers, transhumanists,[83][84] and professionals in various sectors. Its use is attributed by these individuals to its potential for enhancing attention, cognitive capabilities, and alertness.[85][86]

The effectiveness of modafinil as a cognitive enhancer is still debated. Some studies suggest significant increases in cognitive abilities, while others indicate mild to nonexistent cognitive improvements.[87][88][58][89] In some cases, it has even been associated with impairments in certain cognitive functions.[21][22][90] It has been shown that modafinil's positive impact on cognitive abilities is more noticeable on sleep-deprived individuals.[91] Therefore, in people who are not sleep-deprived, the potential of modafinil as a cognitive enhancer may be limited.[92]

Adverse effects

[edit]Modafinil is generally well-tolerated but can have potential risks and side effects. Common adverse effects of modafinil, experienced by less than 10% of users, include headaches, nausea, and reduced appetite.[93][94][20] Anxiety, insomnia, dizziness, diarrhea, and rhinitis are also reported in 5% to 10% of users.[20] Psychiatric reactions have occurred in individuals with and without a preexisting psychiatric history.[95]

No significant changes in body weight have been observed in clinical trials, although decreased appetite and weight loss have been noted in children and adolescents.[96] Modafinil can cause a slight increase in aminotransferase enzymes, indicative of liver function, but there is no evidence of serious liver damage when levels are within reference ranges.[97]

Rare but serious adverse effects include severe skin rashes and allergy-related symptoms. Between December 1998 and January 2007, the FDA received reports of six cases of severe cutaneous adverse reactions, including erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and DRESS syndrome. The FDA has issued alerts regarding these risks and also noted reports of angioedema and multi-organ hypersensitivity reactions in postmarketing surveillance.[98][99] In 2007, the FDA required Cephalon to modify the Provigil leaflet to include warnings about these serious conditions. The long-term safety and effectiveness of modafinil have not been conclusively established.[100]

The FDA does not endorse modafinil for children's medical conditions due to an increased risk of rare but serious dermatological toxicity, manifested as Stevens–Johnson syndrome which is a type of severe skin reaction.[101][65][102] However, in Europe, modafinil may be prescribed for treating narcolepsy in children.[103]

Available forms

[edit]

Modafinil is commercially available in 100 mg and 200 mg oral tablet forms.[8] Additionally, it is offered as the (R)-enantiomer, known as armodafinil, and as a prodrug named adrafinil.[104]

Contraindications

[edit]Modafinil is contraindicated during pregnancy and 2 months before getting pregnant.[105] Women who take modafinil should not become pregnant, and, additionally, should be aware that modafinil reduces effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives, increasing chances of getting pregnant.[8][15][106] Modafinil therapy during pregnancy increases the risk of birth defects,[17][107][108][105] such as with congenital torticollis, hypospadias, and congenital heart defects.[107]

Modafinil is contraindicated for individuals with known hypersensitivity to either modafinil or armodafinil.[8][13]

Modafinil is also contraindicated in certain cardiac conditions, including uncontrolled moderate to severe hypertension, arrhythmia, cor pulmonale,[109][110] and in cases with signs of CNS stimulant-induced mitral valve prolapse or left ventricular hypertrophy.[111][112] The package insert in the United States cautions about using modafinil in people with a documented medical history of left ventricular hypertrophy or those diagnosed with mitral valve prolapse who have previously exhibited symptoms associated with the mitral valve prolapse syndrome while undergoing treatment involving central nervous system stimulants.[113] The reasons why modafinil is contraindicated in certain cardiac conditions are because modafinil affects the autonomic nervous system and, in particular, exerts significant effects on autonomic cardiovascular regulation, leading in some people to notable increases in heart rate and blood pressure. These substantial changes in the autonomic system warrant careful consideration when prescribing modafinil to people with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions.[114] The increase in heart rate and blood pressure can worsen the symptoms of such pre-existing conditions as hypertension, arrhythmia, and cor pulmonale. These changes in the autonomic system induced by modafinil can increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, and heart failure. Modafinil can stimulate the release of norepinephrine and epinephrine, hormones that activate the sympathetic nervous system. This can cause vasoconstriction, which is the narrowing of blood vessels, and increase the heart's workload, which is not desired in people with pre-existing heart conditions. In particular, modafinil can worsen the consequences of mitral valve prolapse or left ventricular hypertrophy, which are structural abnormalities of the heart. These can affect the blood flow and oxygen delivery to the heart and other organs.[115]

Modafinil is also contraindicated in people with congenital problems like galactose intolerance, lactase deficiency, or glucose-galactose malabsorption.[116][109][110]

Drug tolerance

[edit]Extensive clinical research has not demonstrated drug tolerance as a common adverse effect, even with therapeutic use extending up to 40 weeks.[117][118][100] Drug tolerance in this context is defined as a reduction in response, to wakefulness-promoting and anti-fatigue properties of modafinil.[117]

While modafinil is generally found to be safe and significant adverse effects are rare, including in pediatric narcolepsy cases (sleep disorders in children), there is evidence that long-term usage can lead to tolerance in some individuals.[22] This necessitates higher doses to maintain the same level of cognitive enhancement or relief from sleepiness.[22]

People with current or past substance addictions and those with a family history of addiction are particularly at risk for developing tolerance.[22][103][119]

The mechanisms driving tolerance to modafinil, which may involve its impact on dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain, are not fully understood.[22][103][119]

Repeated administration of modafinil for off-label use, such as increased alertness and cognitive-enhancing effects in sleep deprivation, can lead to drug tolerance, which means that the effectiveness of the drug may decrease over time. Still, modafinil therapy as a eugeroic agent to treat narcolepsy does not typically lead to drug tolerance, i.e., the effectiveness does not usually decrease on prolonged use, although individual responses may vary.[22][103][119]

Addiction and dependence

[edit]Despite being a CNS stimulant, the addiction and dependence liabilities of modafinil are considered low.[8][2][25][120] The exact mechanisms of action of modafinil are not known,[121] and it is believed that pharmacological profile of modafinil is different from that of the classical stimulants such as cocaine or amphetamine.[13] Although modafinil shares biochemical mechanisms with stimulant drugs, it is less likely to have mood-elevating properties.[8] The similarities in effects with caffeine are not clearly established.[13][122] Unlike other stimulants, modafinil does not induce a strong subjective feeling of pleasure or reward, which is commonly associated with euphoria, an intense feeling of well-being.[22] Euphoria may be an indicator of a drug's potential to be abused. Substance abuse is a compulsive and excessive use of the substance despite adverse consequences.[123] In comparison to classical stimulants, modafinil exhibits a low propensity for abuse, as it lacks significantly expressed pleasurable or euphoric effects.[22] Albeit to a lower degree than classical stimulants, modafinil still can produce psychoactive, euphoric, and subjective effects typical for abused stimulants.[8][3]

Modafinil was not observed to promote overuse or misuse, even in people who have a history of cocaine addiction.[124] Despite the initial belief that modafinil carried no abuse potential, emerging evidence suggests that it works at the same neurobiological mechanisms as other addictive stimulants. Consequently, there exists a potential risk of modafinil abuse, necessitating prudent consideration and caution when prescribing or using this medication.[92] Modafinil exhibits a lower response on the amphetamine scale of the addiction research center inventory, suggesting reduced propensity for abuse compared to amphetamine.[125]

The US Drug Enforcement Administration has classified modafinil as a Schedule IV controlled substance;[2][8] the medicine is recognized for having valid medical uses with low addiction potential.[120][54] The International Narcotics Control Board does not classify it as a narcotic or a psychotropic substance.[126][127]

Overdose

[edit]An overdose of modafinil can lead to a range of symptoms and complications. Psychiatric symptoms may include psychosis, mania, hallucinations, and suicidal ideation, which can occur even in individuals without a history of mental illness and may persist after discontinuation of the drug.[128] Neurological complications, such as seizures, tremors, dystonia, and dyskinesia, may arise from modafinil's interaction with various neurotransmitter systems.[128]

Allergic reactions such as rash, angioedema, anaphylaxis, and Stevens–Johnson syndrome may rarely be triggered by an immunological response to modafinil or its metabolites.[129][130] Cardiovascular complications like hypertension, tachycardia, chest pain, and arrhythmias may also be observed due to modafinil's sympathomimetic action.[128]

In animal studies, the median lethal dose (LD50) of modafinil varies among species and depends on the route of administration. In mice and rats, the LD50 is approximately 1250 mg/kg if administered via an injection, but the oral LD50 for rats is 3400 mg/kg.[131][132] The LD50 value for humans have not been established. Human clinical trials have involved total daily doses up to 1200 mg/d for 7–21 days. Acute one-time total overdoses up to 4500 mg have not been life-threatening but resulted in symptoms like agitation, insomnia, tremor, palpitations, and gastrointestinal disturbances.[8][133]

The management of modafinil overdose involves supportive care, monitoring of vital signs, and treatment of specific complications. In cases of recent consumption, activated charcoal, gastric lavage, or hemodialysis may be used.[128] There is no specific antidote for modafinil overdose.[133][134][135] The main way to deal with modafinil overdose is supportive care, which includes sedating the patient and stabilizing their blood pressure, and muscle activity in case of manifestations such as agitation or tremor.[133]

Interactions

[edit]Some of the drugs that frequently interact with modafinil include aripiprazole (an antipsychotic), amphetamine (including its enantiomers and salts; stimulants), aspirin, diphenhydramine (an antihistamine), and others.[136]

Modafinil is a weak to moderate inducer of CYP3A4[106][137][138] and a weak inhibitor of CYP2C19,[11] enzymes of the cytochrome P450 group of enzymes.[20] Modafinil also induces or inhibits other cytochrome P450 enzymes.[106] One in vitro study predicts that modafinil may induce the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP1A2, CYP3A4, and CYP2B6, as well as may inhibit CYP2C9 and CYP2C19.[14] However, other in-vitro studies find no significant inhibition of CYP2C9.[11][139] Modafinil may induce P-glycoprotein, which may affect drugs transported by P-glycoprotein, such as digoxin.[140] It was clinically found that modafinil affects pharmacodynamics of drugs which are metabolized by CYP3A4 and other enzymes of the cytochrome P450 family so that interactions of modafinil with these drugs were observed in real people, rather than being predicted in a lab setting.[106][137] For instance, it was observed that induction of CYP3A4 by modafinil affects metabolism of the following medications and endogenous substances:[141]

- opioids, such as methadone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, or fentanyl – modafinil may result in a drop in opioid plasma concentrations because of faster clearance of opioids by CYP3A4. If the patient is not monitored closely, reduced efficacy or withdrawal symptoms can occur.[141]

- steroid hormones, such as estradiol, progesterone or cortisol. Modafinil may have an adverse effect on hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, patches, etc.) for up to a month after discontinuation.[142] Both modafinil and armodafinil in the United States and the United Kingdom come with package inserts that highlight the interaction between these medications and hormonal birth control.[106] Modafinil may induce cytochrome P450 enzymes that are involved in the clearance of steroid hormones taken as hormonal contraceptives, reducing their effectiveness, which may lead to pregnancy despite taking the birth control medication. Besides steroid hormones, modafinil may affect pituitary gland hormones. In a 2006 study, a single dose of modafinil 200 mg caused a decrease in blood prolactin levels, although it did not affect human growth hormone or thyroid-stimulating hormone.[87][143] Since modafinil induces the activity of the CYP3A4 enzyme involved in cortisol clearance,[144] modafinil may reduce the bioavailability of hydrocortisone. Therefore, it may be necessary to adjust the steroid substitution dose in people receiving modafinil, which is a CYP3A4-metabolism-inducing drug.[145]

Hypertensive crises have been reported when armodafinil (one of modafinil's enantiomers) has been taken with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) like tranylcypromine.[146]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Site | Potency | Type | Species | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | 1.8–2.6 μM 4.8 μM 6.4 μM 4.0 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[147][148] [147] [149][150] [147] |

| NET | >10 μM >92 μM 35.6 μM 136 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[147][148] [147] [149][150] [147] |

| SERT | >10 μM 46.6 μM >500 μM >50 μM |

Ki Ki IC50a IC50a |

Human Rat Human Rat |

[147][148] [147] [149][150] [147] |

| D2 | >10 μM 16 μMb 120 μMb |

Ki Ki EC50a |

Human Rat Rat |

[147] [151] [151] |

| Footnotes: a = Functional activity, not binding inhibition. b = Armodafinil at D2High. Notes: No activity at a variety of other assessed targets.[147] | ||||

The precise mechanism of action of modafinil for narcolepsy and other sleep disorders remains unclear.[3][121][152][153] Although modafinil may have interactions with neurotransmitter systems, its exact mode of action is not fully understood.[121][154]

From laboratory research, modafinil has little to no affinity for serotonin or norepinephrine transporters and does not directly interact with these systems.[20][153] However, studies have shown that elevated concentrations of norepinephrine and serotonin can occur as an indirect effect following modafinil administration due to increased extracellular dopamine activity.[153][20] Unlike traditional psychostimulant drugs,[23] such as cocaine or amphetamine, modafinil shows low potential for causing euphoria due to differences in how it interacts with dopamine transporters at a cellular level.[121][153][154]

In addition to its influence on dopaminergic pathways, modafinil may impact other neurotransmitter systems, such as orexin (hypocretin).[153] Orexin neurons are involved in promoting wakefulness and regulating arousal states. Modafinil may increase signaling within hypothalamic orexin pathways, potentially contributing to its wake-promoting effects.[20][153]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Cmax (peak levels) occurs approximately 2 to 3 hours after modafinil administration.[11] Food slows the absorption of modafinil but does not affect the total area under the curve (AUC). In vitro measurements indicate that 60% of modafinil is bound to plasma proteins at clinical concentrations of the drug. This percentage changes very little when the concentration of modafinil is varied.[155]

Renal excretion of unchanged modafinil usually accounts for less than 10% of an oral dose. This means that when modafinil is taken by mouth, that is the only approved route of administration, less than 10% of the drug is eliminated from the body through the urine without being metabolized by the liver or other organs. The rest of the drug is either metabolized or excreted through other routes, such as feces or bile.[11]

The two major circulating metabolites of modafinil are modafinil acid (CRL-40467) and modafinil sulfone (CRL-41056). Both of these metabolites have been described as inactive, and neither appears to contribute to the wakefulness-promoting effects of modafinil.[65][156] However, modafinil sulfone does appear to possess anticonvulsant effects, a property that it shares with modafinil.[65][157]

Elimination half-life is in the range of 10 to 12 hours,[11][155] subject to differences in sex,[106] in cytochrome P450 genotypes, liver function and renal function. Modafinil is metabolized mainly in the liver,[11] and its inactive metabolites are excreted in the urine. Urinary excretion of the unchanged drug is usually less than 10% but can range from 0% to as high as 18.7%, depending on the factors mentioned.[155]

Modafinil exhibits sex-specific pharmacokinetic differences.[106] It demonstrates higher bioavailability in women compared to men. The mean Cmax is higher in women than in men, 5.2 mg/L vs. 4.2 mg/L (p < 0.05), following a single 200 mg oral dose of modafinil.[106] This difference persists even after adjusting for body weight (0.88 ml/min/kg vs. 0.72 ml/min/kg).[106] The clearance of modafinil is 30% higher in men than in women, and plasma concentrations after a single dose are significantly higher in women than in men. These sex-specific pharmacokinetic differences may have implications for the efficacy and safety of modafinil.[106]

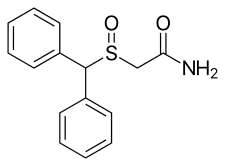

Chemistry

[edit]Enantiomers

[edit]Modafinil is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, armodafinil ((R)-modafinil) and esmodafinil ((S)-modafinil).[158]

Detection in body fluids

[edit]Modafinil and/or its major metabolite, modafinil acid, may be quantified in plasma, serum, or urine to monitor dosage in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, or to assist in the forensic investigation of a vehicular traffic violation.[159] Instrumental techniques involving gas or liquid chromatography are usually employed for these purposes.[89][160][161] In 2011, modafinil was not tested for by common drug screens (except for anti-doping screens) and is unlikely to cause false positives for other chemically unrelated drugs such as substituted amphetamines.[150][158][162]

Reagent testing can screen for the presence of modafinil in samples.[163][164]

| RC | Marquis Reagent | Liebermann | Froehde |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | Yellow/Orange > Brown[163][164] | Darkening Orange[163] | Deep orange/red[164] |

Structural analogs

[edit]Many derivatives and structural analogs of modafinil have been synthesized.[24][165][166] Examples include adrafinil, CE-123, fladrafinil (CRL-40941; fluorafinil), flmodafinil (CRL-40940; bisfluoromodafinil, lauflumide), RDS03-94, JJC8-088, modafiendz and modafinil sulfone (CRL-41056).[167][24]

History

[edit]Modafinil was developed in France by neurophysiology professor Michel Jouvet and Lafon Laboratories. It is part of a series of benzhydryl sulfinyl compounds, including adrafinil, initially used as a treatment for narcolepsy in France in 1986.[168] Modafinil, the primary metabolite of adrafinil,[169] has been prescribed in France since 1994 under the name Modiodal,[168] and in the United States since 1998 as Provigil.[8] Unlike modafinil, adrafinil does not have FDA approval and was withdrawn from the French market in 2011.[170]

The FDA approved modafinil in 1998 for narcolepsy treatment, and later for shift work sleep disorder and obstructive sleep apnea in 2003.[8][171][172] It was approved in the UK in December 2002. In the United States, modafinil is marketed by Cephalon,[173] who acquired the rights from Lafon and purchased the company in 2001.[173]

Cephalon introduced armodafinil, the (R)-enantiomer of modafinil, in the United States in 2007. Generic versions of modafinil became available in the US in 2012 after extensive patent litigation.[174][175]

Society and culture

[edit]Modafinil is not approved for use by children in multiple jurisdictions.[1][176][7][8][177]

Legal status

[edit]Australia

[edit]In Australia, modafinil is considered to be a Schedule 4 prescription-only medicine. This means that it is a drug with a perceived low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence; still, the use of Schedule 4 drugs in Australia is restricted to those who have a valid prescription from a medical practitioner; import from abroad is illegal.[178]

Canada

[edit]In Canada, modafinil is not specifically included in the lists of controlled drugs and substances specified within the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.[179] However, it is classified as a Schedule F prescription drug.[180][181][182] This means that modafinil can only be obtained legally with a valid prescription from a licensed health care practitioner in Canada, and the import of modafinil to Canada from other countries is subject to restrictions: importing prescription drugs without an import permit may result in the seizure of the drugs at the border, the refusal of entry of the drugs into Canada, or prosecution.[183]

China

[edit]In mainland China, modafinil is strictly controlled like other stimulants such as amphetamines and methylphenidate. It is classified as Class I psychotropic drug. This classification means that modafinil is considered to have a high potential for abuse and dependence, and is therefore subject to strict regulation and control. As a result, modafinil is only available by prescription and cannot be purchased over the counter. In order to obtain a prescription for modafinil, a patient must have a valid medical reason for using the drug, such as narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. Additionally, the prescription must be written by a licensed physician and filled at a licensed pharmacy. The use of modafinil for non-medical purposes, such as with the aim to improve cognitive performance or to stay awake for long periods of time, is strictly prohibited and can result in legal consequences.[184][185]

Europe

[edit]In Denmark, modafinil is a prescription drug but not listed as a controlled substance. According to the Danish Medicines Agency, modafinil is approved for use in the treatment of narcolepsy, still, importing modafinil to Denmark is considered illegal without a valid prescription.[186][187][188][189]

In Finland, modafinil is a prescription drug but not listed as a controlled substance. Finland is a member of the European Union, and it is illegal to import prescription medicine from outside the European Union unless the person has a valid prescription.[190][191][192]

In the Republic of Moldova, modafinil is classified as a psychotropic drug (included in table III list 3 which is the list of psychotropic substances as defined by the Government of Moldova)[193] and is available by prescription.[193] Importation of modafinil may be considered illegal and subject to severe penalties, even if you have a prescription.[194] For example, on June 29, 2017, Moldovan postal officers discovered 60 tablets of Modalert (200 mg modafinil tablets) in a parcel sent from India to a resident in Chișinău, Moldova. The prohibited substance was detected during a routine scan and was seized as illegal. The authorities were notified of the incident and the recipient was charged with criminal penalties.[195][196] In the Transnistria region of Moldova, modafinil is completely prohibited, due to application of the legislation similar to that of Russia where modafinil is completely prohibited and is in the same list as narcotics. Possession or an attempt to bring modafinil to Transnistria potentially leads to imprisonment.[197]

In Romania, modafinil is classified as a stimulant doping agent and is prohibited in sports competitions.[198] In 2022, laws were passed making its importation or sale a felony, punishable by three to seven years in jail.[199] Simple possession for personal use may result in a fine and confiscation.[199]

In Sweden, modafinil is classified as a schedule IV substance, which means that it is considered to have a low potential for abuse and a low risk of dependence. Still, possession is illegal without a prescription.[200]

In the United Kingdom, it is not listed in Misuse of Drugs Act, so possession is not illegal, but a prescription is required.[201]

Mexico

[edit]In Mexico, modafinil is not listed as a controlled substance, in the National Health Law, and can be purchased in pharmacies without prescription.[202]

Japan

[edit]In Japan, modafinil is Schedule I psychotropic drug. This means that it is considered to have a high potential for abuse and dependence, and is therefore subject to strict regulations. The use of Schedule I drugs in Japan is generally prohibited, except under certain circumstances, such as for medical purposes. It can only be prescribed by a doctor. It cannot be imported or exported without a permit. It cannot be used while driving or operating machinery.[203][204] Cephalon licensed Alfresa Corporation to produce, and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma to sell modafinil products under the trade name Modiodal in Japan.[205] There have been arrests of people who imported modafinil for personal use.[206][207]

Russia

[edit]In Russia, starting from May 18, 2012, modafinil is Schedule II controlled substance. Being classified as a Schedule II controlled substance in Russia means that it is seen as a drug with a high potential for abuse and dependence. This classification imposes strict regulations on the production, distribution, and use of modafinil. Possession of a few modafinil pills can lead to three to ten years imprisonment. Modafinil is not approved for medical use in Russia and cannot be bought even in pharmacies. It also cannot be imported from abroad, even if you have a prescription issued outside Russia.[197][208] There are multiple cases of criminal proceedings initiated against Russian residents who tried to import modafinil by mail from abroad.[209][210]

South Africa

[edit]In South Africa, modafinil is Schedule V substance, which means that it is legal to use modafinil in South Africa, but only with a valid prescription from a licensed medical practitioner.[211]

United States

[edit]In the United States, modafinil is classified as a schedule IV controlled substance[2] under US federal law.[8][212] This means that the drug has a low potential for abuse and dependence compared to other controlled substances. However, it still requires a prescription from a licensed healthcare provider to obtain.[212]

It is illegal to import modafinil to the United States without a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)–registered importer and a prescription.[213] Individuals may legally bring modafinil into the US from a foreign country for personal use, limited to 50 dosage units, with a prescription and proper declaration at the border.[214] Under the Pure Food and Drug Act, marketing drugs for off-label uses is prohibited.[215] Cephalon, the manufacturer of Provigil, faced legal issues for promoting off-label uses and paid significant fines in 2008.[216]

Brand names

[edit]

Modafinil is sold under a variety of brand names worldwide, including Alertec, Alertex, Altasomil, Aspendos, Bravamax, Forcilin, Intensit, Karim, Mentix, Modafinilo, Modalert, Modanil, Modasomil, Modvigil, Modiodal, Modiwake, Movigil, Provigil, Resotyl, Stavigile, Vigia, Vigicer, Vigil, Vigimax, Waklert, and Zalux.[217]

Economics

[edit]Originally developed in the 1970s by French neuroscientist Michel Jouvet and Lafon Laboratories, modafinil has been prescribed in France since 1994,[168][36] and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1998.[8][36]

Concerns have been raised about the growing use of modafinil as a "smart drug" or cognitive enhancer among healthy individuals who use it with the aim to improve concentration and memory.[218][219] In 2003, modafinil sales were skyrocketing, with some experts concerned that it had become a tempting pick-me-up for people looking for an extra edge in a productivity-obsessed society.[218] The cost of modafinil varied depending on factors such as location and insurance coverage;[218][219][220] still, in 2004, the price of modafinil in the US was around $120 or more per monthly supply.[218] However, the availability of generic versions has increased since then and may have driven down prices.[218][219][220]

In 2020, modafinil was the 302nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with just over 1,000,000 prescriptions.[221]

As of 2024,[update] the global sales figures for modafinil are not known. Still, modafinil sold under the brand name Provigil accounted for over 40% of Cephalon's global turnover for several years, according to the information published in 2020.[222]

Patent protection and litigation

[edit]Modafinil's patent history involves several key developments. The original patent, U.S. patent 4,927,855, was granted to Laboratoire L. Lafon in 1990, covering the chemical compound of modafinil. This patent expired in 2010.[223] In 1994, Cephalon filed a patent for modafinil in the form of particles of a defined size, represented by U.S. patent 5,618,845, which expired in 2015.[224]

Following the nearing expiration of marketing rights in 2002, generic manufacturers, including Mylan and Teva, applied for FDA approval to market a generic form of modafinil, leading to legal challenges by Cephalon regarding the particle size patent.[225] The patent RE 37,516 was declared invalid and unenforceable in 2011.[226]

In addition, Cephalon entered agreements with several generic drug manufacturers to delay the sale of generic modafinil in the US. These agreements were subject to legal scrutiny and antitrust investigations, culminating in a ruling by the Court of Appeals in 2016, which found that the settlements did not violate antitrust laws.[227]

Sports

[edit]The regulation of modafinil as a doping agent has been controversial in the sporting world, with high-profile cases attracting press coverage since several prominent American athletes tested positive for the substance. Some athletes who used modafinil protested that the drug was not on the prohibited list at the time of their offenses.[228] However, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) maintains that modafinil was related to already-banned substances. The Agency added modafinil to its list of prohibited substances on August 3, 2004, ten days before the start of the 2004 Summer Olympics.[162]

Several athletes, such as sprinter Kelli White in 2003,[229] cyclist David Clinger[230] and basketball player Diana Taurasi[231] in 2010, and rower Timothy Grant in 2015,[232] were accused of using modafinil as a performance-enhancing doping agent. Taurasi and another player—Monique Coker, tested at the same lab—were later cleared.[233] Kelli White, who tested positive after her 100m victory at the 2003 World Championships in Paris, was stripped of her gold medals.[234] She claimed that she used modafinil to treat narcolepsy, but the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) ruled that modafinil was a performance-enhancing drug.[234]

The BALCO scandal brought to light an unsubstantiated (but widely published) account of Major League Baseball's all-time leading home-run hitter Barry Bonds' supplemental chemical regimen that included modafinil in addition to anabolic steroids and human growth hormone.[235]

Social views

[edit]The use of modafinil as a supposed cognitive enhancer may be considered as cheating, unnatural, or risky.[236] The University of Sussex explained that it is a prescription drug and the decision should be made by the doctor on whether to prescribe modafinil to a student.[237] As a matter of bioethics, the US President's Council on Bioethics argued that excellence achieved through the use of drugs like modafinil is "cheap" as it obviates the need for hard work and study, and is not fully authentic because the excellence is partly attributable to the drug, not the individual.[238] Alternately, people in environments like Wall Street trading may not view the use of modafinil as cheating, believing that if modafinil can give them an edge and they are aware of the risks involved, it should not be considered as cheating.[239] Due to such varying views, modafinil users for narcolepsy may cope with stigma by hiding, denying, or justifying their use, or by seeking support from others who share their views or experiences.[240][241]

Research

[edit]Psychiatric conditions

[edit]Major depressive disorder

[edit]Modafinil has been studied in the treatment of major depressive disorder.[242][243][244] In a 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of psychostimulants for depression, modafinil and other stimulants such as methylphenidate and amphetamines improved depression in traditional meta-analysis.[244] However, when subjected to network meta-analysis, modafinil and most other stimulants did not significantly improve depression, with only methylphenidate remaining effective.[244] Modafinil and other stimulants likewise did not improve quality of life in the meta-analysis, although there was evidence for reduced fatigue and sleepiness with modafinil and other stimulants.[244] While significant effectiveness of modafinil for depression has been reported by particular trials,[70][243][245] reviews and meta-analyses note that the effectiveness of modafinil for depression is limited, the quality of available evidence is low, and the results are inconclusive.[244][246][247]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (research)

[edit]Modafinil was considered for the treatment of ADHD because of its lower abuse potential than conventional psychostimulants[23] like methylphenidate and amphetamines.[55][248] In 2008, an application to market modafinil for pediatric ADHD was submitted to the Food and Drug Administration in the US.[93][49]

However, evidence of modafinil for treatment of adult ADHD is mixed, and a 2016 systematic review of alternative drug therapies for adult ADHD did not recommend its use in this context.[51] In a later large phase 3 clinical trial of modafinil for adult ADHD, modafinil was not effective in improving symptoms, there was also a high rate of side effects (86%) and discontinuation (47%).[249] The poor tolerability of modafinil in this study was possibly due to the use of high doses (210–510 mg/d).[249] Another reason for the denial of the approval was due to concerns about rare but serious dermatological toxicity in Stevens–Johnson syndrome.[93]

The research on the use of modafinil for treating individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) who also exhibit ADHD symptoms is currently in its early stages with no results delivered.[250]

Substance dependence

[edit]Modafinil was studied for the treatment of stimulant dependence, but the results are mixed and inconclusive.[24][251] Modafinil is not a controlled substance in some countries, unlike other medications, such as bupropion, which is also used to treat depression and nicotine dependence.[252] The clinical trials that have tested modafinil as a treatment for stimulant abuse have failed to demonstrate its efficacy and the optimal dose and duration of modafinil treatment remain unclear, and modafinil is not a recommended treatment for stimulant abuse.[252] 2024 reviews found that modafinil was ineffective for treating individuals with amphetamine-type stimulant use disorder[253] or methamphetamine use disorder[254] from these dependencies.[254][253]

Schizophrenia

[edit]Modafinil and armodafinil were studied as a complement to antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia. They showed no effect on positive symptoms or cognitive performance.[255][256] A 2015 meta-analysis found that modafinil and armodafinil may slightly reduce negative symptoms in people with acute schizophrenia, though they do not appear useful for people with the condition who are stable, with high negative symptom scores.[256] Among medications demonstrated to be effective for reducing negative symptoms in combination with antipsychotics, modafinil, and armodafinil are among the smallest effect sizes.[257]

Abstinence in cocaine addiction

[edit]Modafinil is researched to determine whether it might improve abstinence in people with cocaine addiction.[258]

Motivational disorders

[edit]Modafinil has been found to reverse tetrabenazine-induced motivational deficits in animals and hence can produce pro-motivational effects.[259][260][261] Novel modafinil analogs with greater potency, including CE-123, CE-158, JJC8-088, MK-26, and RDS03-94, have also been developed and have shown pro-motivational effects in animals.[259][262] These agents are of potential interest in the treatment of motivational disorders in humans.[259][262]

Cognitive enhancement

[edit]A 2019 review conducted on the potential nootropic effects of modafinil in healthy, non-sleep-deprived individuals revealed the following:[263] a) while studies using basic testing paradigms demonstrated that modafinil enhances executive function, only half of these studies showed improvements in attention, learning, and memory, with a few studies even reporting impairments in divergent creative thinking; b) modafinil displayed small levels of enhancement in attention, executive functions, and learning abilities; c) no substantial side effects or mood changes were observed; d) the available evidence showed limited evidence for modafinil as a cognitive enhancer outside of its use for sleep-deprived populations.

A 2020 review reported that modafinil has a modest effect on memory updating, but the effect is small and may not accurately reflect the perception that it is useful as a cognitive enhancer, as there is insufficient evidence to support such a claim.[264]

Post-anesthesia sedation

[edit]General anesthesia is required for many surgeries, but may cause lingering fatigue, sedation, and/or drowsiness after surgery that lasts for hours to days.[265][266] In outpatient surgery the sedation, fatigue, and occasional dizziness is problematic.[267][268] Modafinil was tested as a potential remedy to alleviate these symptoms.[54] For example, it was expected that modafinil would help people recover quicker from general anesthesia after a short surgery,[93] but the results were uncertain and the inconclusive studies could not reliably verify the expectation.[54] The use of modafinil to relieve post-anesthesia sedation is investigational.[93]

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

[edit]Caution should be exercised in people who have narcolepsy in comorbidity with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).[269]

Myotonic dystrophy

[edit]Modafinil is being researched as a potential remedy for excessive daytime sleepiness in myotonic dystrophy (DM), an inherited condition characterized by progressive muscle loss, weakness, and myotonia. Myotonia is a condition where muscles cannot relax after they contract.[270] Myotonic dystrophy has two main types: DM1 (Steinert disease) and DM2 (proximal myotonic myopathy). Both types can cause excessive daytime sleepiness. Studies suggest that modafinil may be a promising drug that can reduce both daytime sleepiness and myotonia itself, without significant cardiac conduction effects. These presumed property of modafinil is of particular interest for evntual treatment of pepole with myotonic dystrophy who often have underlying cardiac issues.[270] Still, modafinil is not approved by the FDA for use in myotonic dystrophy, and the value and role of modafinil in DM remain the subject of debate.[270]

Disorders of consciousness

[edit]Modafinil has been studied for its potential therapeutic effects in patients with disorders of consciousness.[271] Researchers are investigating whether modafinil can stimulate neurotransmitters such as histamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, and orexin, and whether modafinil has potential anti-oxidative effects.[271]

Disorders of consciousness are states characterized by impaired arousal and awareness.[271] These states include coma, vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (VS/UWS), minimally conscious state (MCS), cognitive motor dissociation, and covert cortical processing.[271] Brain injuries can impair consciousness through neuroanatomic lesions involving the bilateral cerebral hemispheres, rostral brainstem, diencephalon, or basal forebrain.[271]

Neuroimaging studies have shown that modafinil increases cerebral blood flow in several brain regions, such as the thalamus, locus coeruleus, limbic system, and insular cortex;[271] still, observational reports on the use of modafinil in patients with disorders of consciousness have produced mixed results, indicating that its effectiveness may vary among individuals.[271]

Inflammation

[edit]A possible link between inflammatory processes and depressive disorders[272] has stimulated preliminary research on modafinil for its potential anti-inflammatory effects.[273]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "TGA eBS - Product and Consumer Medicine Information Licence". Archived from the original on February 28, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Sapienza F (January 27, 1999). "64 FR 4050 - Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Modafinil Into Schedule IV". Federal register. Department of Justice. Archived from the original on February 5, 2024. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Modafinil Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. September 23, 2023. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "RDC Nº 784 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published April 4, 2023). March 31, 2023. Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Modafinil Product information". Health Canada. April 25, 2012. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "Modafinil Provigil 100 mg Tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SMPC) – (Emc)". emc. June 9, 2021. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Provigil- modafinil tablet". DailyMed. November 30, 2018. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sousa A, Dinis-Oliveira RJ (2020). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic of the cognitive enhancer modafinil: Relevant clinical and forensic aspects". Subst Abus. 41 (2): 155–173. doi:10.1080/08897077.2019.1700584. PMID 31951804.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hersey M, Tanda G (2024). "Modafinil, an atypical CNS stimulant?". Pharmacological Advances in Central Nervous System Stimulants. Adv Pharmacol. Vol. 99. pp. 287–326. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2023.10.006. ISBN 978-0-443-21933-7. PMID 38467484.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Robertson P, Hellriegel ET (2003). "Clinical pharmacokinetic profile of modafinil". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 42 (2): 123–137. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342020-00002. PMID 12537513. S2CID 1266677.

- ^ a b c Niemegeers P, Maudens KE, Morrens M, Patteet L, Joos L, Neels H, et al. (September 2012). "Pharmacokinetic evaluation of armodafinil for the treatment of bipolar depression". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 8 (9): 1189–1197. doi:10.1517/17425255.2012.708338. PMID 22803602.

- ^ a b c d e Kim D (2012). "Practical use and risk of modafinil, a novel waking drug". Environmental Health and Toxicology. 27: e2012007. doi:10.5620/eht.2012.27.e2012007. PMC 3286657. PMID 22375280.

- ^ a b Robertson P, DeCory HH, Madan A, Parkinson A (June 2000). "In vitro inhibition and induction of human hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes by modafinil". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 28 (6): 664–671. PMID 10820139.

- ^ a b c "Modafinil". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. February 15, 2016. Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Maski K, Trotti LM, Kotagal S, Robert Auger R, Rowley JA, Hashmi SD, et al. (September 2021). "Treatment of central disorders of hypersomnolence: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 17 (9): 1881–1893. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9328. PMC 8636351. PMID 34743789.

- ^ a b Kaplan S, Braverman DL, Frishman I, Bartov N (February 2021). "Pregnancy and Fetal Outcomes Following Exposure to Modafinil and Armodafinil During Pregnancy". JAMA Internal Medicine. 181 (2): 275–277. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4009. PMC 7573789. PMID 33074297.

- ^ a b Slotnik DE. "Smart drugs". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Slotnik DE (October 11, 2017). "Michel Jouvet, Who Unlocked REM Sleep's Secrets, Dies at 91". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Greenblatt K, Adams N (February 2022). "Modafinil". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30285371. NCBI NBK531476.

- ^ a b Zamanian MY, Karimvandi MN, Nikbakhtzadeh M, Zahedi E, Bokov DO, Kujawska M, et al. (2023). "Effects of Modafinil (Provigil) on Memory and Learning in Experimental and Clinical Studies: From Molecular Mechanisms to Behaviour Molecular Mechanisms and Behavioural Effects". Current Molecular Pharmacology. 16 (4): 507–516. doi:10.2174/1874467215666220901122824. PMID 36056861. S2CID 252046371.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hashemian SM, Farhadi T (2020). "A review on modafinil: the characteristics, function, and use in critical care". Journal of Drug Assessment. 9 (1): 82–86. doi:10.1080/21556660.2020.1745209. PMC 7170336. PMID 32341841.

- ^ a b c Cid-Jofré V, Bahamondes T, Zúñiga Correa A, Ahumada Arias I, Reyes-Parada M, Renard GM (2024). "Psychostimulants and social behaviors". Front Pharmacol. 15: 1364630. doi:10.3389/fphar.2024.1364630. PMC 11079219. PMID 38725665.

- ^ a b c d Tanda G, Hersey M, Hempel B, Xi ZX, Newman AH (February 2021). "Modafinil and its structural analogs as atypical dopamine uptake inhibitors and potential medications for psychostimulant use disorder". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 56: 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2020.07.007. PMC 8247144. PMID 32927246.

- ^ a b Kakehi S, Tompkins DM (October 2021). "A Review of Pharmacologic Neurostimulant Use During Rehabilitation and Recovery After Brain Injury". Ann Pharmacother. 55 (10): 1254–1266. doi:10.1177/1060028020983607. PMID 33435717. S2CID 231593912.

- ^ Barateau L, Pizza F, Plazzi G, Dauvilliers Y (August 2022). "Narcolepsy". Journal of Sleep Research. 31 (4): e13631. doi:10.1111/jsr.13631. PMID 35624073. S2CID 251107306.

- ^ Anderson D (June 2021). "Narcolepsy: A clinical review". JAAPA. 34 (6): 20–25. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000750944.46705.36. PMID 34031309. S2CID 241205299.

- ^ a b "Modafinil (Provigil): Now restricted to narcolepsy". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ Kallweit U, Bassetti CL (June 2017). "Pharmacological management of narcolepsy with and without cataplexy". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 18 (8): 809–817. doi:10.1080/14656566.2017.1323877. PMID 28443381. S2CID 1906751.

- ^ Wang Y, Zhang W, Ye H, Xiao Y (August 2024). "Excessive daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea: Indirect treatment comparison of wake-promoting agents in patients adherent/nonadherent to primary OSA therapy". Sleep Med Rev. 78: 101997. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2024.101997. PMID 39243682.

- ^ Neshat SS, Heidari A, Henriquez-Beltran M, Patel K, Colaco B, Arunthari V, et al. (August 2024). "Evaluating pharmacological treatments for excessive daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea: A comprehensive network meta-analysis and systematic review". Sleep Med Rev. 76: 101934. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2024.101934. PMID 38754208.

- ^ Morgenthaler TI, Lee-Chiong T, Alessi C, Friedman L, Aurora RN, Boehlecke B, et al. (November 2007). "Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report". Sleep. 30 (11): 1445–1459. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.11.1445. PMC 2082098. PMID 18041479.

- ^ Miano S, Kheirandish-Gozal L, De Pieri M (December 2024). "Comorbidity of obstructive sleep apnea and narcolepsy: A challenging diagnosis and complex management". Sleep Med X. 8: 100126. doi:10.1016/j.sleepx.2024.100126. PMC 11462365. PMID 39386319.

- ^ "Modafinil: Restricted use recommended". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ Arnulf I, Thomas R, Roy A, Dauvilliers Y (June 2023). "Update on the treatment of idiopathic hypersomnia: Progress, challenges, and expert opinion". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 69: 101766. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101766. PMID 36921459. S2CID 257214950. Archived from the original on August 6, 2024. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c Winter Y, Lang C, Kallweit U, Apel D, Fleischer V, Ellwardt E, et al. (December 2023). "Pitolisant-supported bridging during drug holidays to deal with tolerance to modafinil in patients with narcolepsy". Sleep Med. 112: 116–121. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2023.10.005. PMID 37839272.

- ^ "Multiple sclerosis in adults: Management, Guidance". The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ "Provigil". National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Ayache SS, Serratrice N, Abi Lahoud GN, Chalah MA (2022). "Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: A Review of the Exploratory and Therapeutic Potential of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation". Front Neurol. 13: 813965. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.813965. PMC 9101483. PMID 35572947.

- ^ Oliva Ramirez A, Keenan A, Kalau O, Worthington E, Cohen L, Singh S (December 2021). "Prevalence and burden of multiple sclerosis-related fatigue: a systematic literature review". BMC Neurol. 21 (1): 468. doi:10.1186/s12883-021-02396-1. PMC 8638268. PMID 34856949.

- ^ a b c d Ciancio A, Moretti MC, Natale A, Rodolico A, Signorelli MS, Petralia A, et al. (July 2023). "Personality Traits and Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Review". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 12 (13): 4518. doi:10.3390/jcm12134518. PMC 10342558. PMID 37445551.

- ^ a b c MacAllister WS, Krupp LB (May 2005). "Multiple sclerosis-related fatigue". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 16 (2): 483–502. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2005.01.014. PMID 15893683.

- ^ a b c d Ghazanfar S, Farooq M, Qazi SU, Chaurasia B, Kaunzner U (July 2024). "The use of modafinil for the treatment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials". Brain Behav. 14 (7): e3623. doi:10.1002/brb3.3623. PMC 11237168. PMID 38988104.

- ^ a b Brown JN, Howard CA, Kemp DW (June 2010). "Modafinil for the treatment of multiple sclerosis-related fatigue". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 44 (6): 1098–1103. doi:10.1345/aph.1M705. PMID 20442351. S2CID 207263842.

- ^ a b c Shangyan H, Kuiqing L, Yumin X, Jie C, Weixiong L (January 2018). "Meta-analysis of the efficacy of modafinil versus placebo in the treatment of multiple sclerosis fatigue". Mult Scler Relat Disord. 19: 85–89. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2017.10.011. PMID 29175676.

- ^ Wilms W, Woźniak-Karczewska M, Corvini PF, Chrzanowski Ł (October 2019). "Nootropic drugs: Methylphenidate, modafinil and piracetam - Population use trends, occurrence in the environment, ecotoxicity and removal methods - A review". Chemosphere. 233: 771–785. Bibcode:2019Chmsp.233..771W. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.016. PMID 31200137. S2CID 189861826.

- ^ Kittel-Schneider S, Quednow BB, Leutritz AL, McNeill RV, Reif A (May 2021). "Parental ADHD in pregnancy and the postpartum period - A systematic review" (PDF). Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 124: 63–77. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.002. PMID 33516734. S2CID 231723198. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- ^ Weiergräber M, Ehninger D, Broich K (April 2017). "Neuroenhancement and mood enhancement – Physiological and pharmacodynamical background". Medizinische Monatsschrift Fur Pharmazeuten. 40 (4): 154–164. PMID 29952165.

- ^ a b c d Miskowiak KW, Obel ZK, Guglielmo R, Bonnin CD, Bowie CR, Balanzá-Martínez V, et al. (May 2024). "Efficacy and safety of established and off-label ADHD drug therapies for cognitive impairment or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in bipolar disorder: A systematic review by the ISBD Targeting Cognition Task Force" (PDF). Bipolar Disord. 26 (3): 216–239. doi:10.1111/bdi.13414. PMID 38433530.

- ^ Stuhec M, Lukić P, Locatelli I (February 2019). "Efficacy, Acceptability, and Tolerability of Lisdexamfetamine, Mixed Amphetamine Salts, Methylphenidate, and Modafinil in the Treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 53 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1177/1060028018795703. PMID 30117329. S2CID 52019992.

- ^ a b Buoli M, Serati M, Cahn W (2016). "Alternative pharmacological strategies for adult ADHD treatment: a systematic review". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 16 (2): 131–144. doi:10.1586/14737175.2016.1135735. PMID 26693882. S2CID 33004517.

- ^ Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, Mohr-Jensen C, Hayes AJ, Carucci S, et al. (September 2018). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (9): 727–738. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4. PMC 6109107. PMID 30097390.

- ^ Rodrigues R, Lai MC, Beswick A, Gorman DA, Anagnostou E, Szatmari P, et al. (June 2021). "Practitioner Review: Pharmacological treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 62 (6): 680–700. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13305. PMID 32845025. S2CID 221329069.

- ^ a b c d Ballon JS, Feifel D (April 2006). "A systematic review of modafinil: Potential clinical uses and mechanisms of action". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (4): 554–566. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0406. PMID 16669720.

- ^ a b Turner D (April 2006). "A review of the use of modafinil for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 6 (4): 455–468. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.4.455. PMID 16623645. S2CID 24293088.

- ^ Lindsay SE, Gudelsky GA, Heaton PC (October 2006). "Use of modafinil for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (10): 1829–1833. doi:10.1345/aph.1H024. PMID 16954326. S2CID 37368284.

- ^ Bond DJ, Hadjipavlou G, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A, et al. (February 2012). "The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 24 (1): 23–37. PMID 22303520.

- ^ a b Retz W (2022). "Efficacy of Amphetamines, Methylphenidate, and Modafinil in the Treatment of Mental Disorders". NeuroPsychopharmacotherapy. pp. 2465–2486. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-62059-2_319. ISBN 978-3-030-62058-5.

- ^ Dell'Osso B, Ketter TA (February 2013). "Use of adjunctive stimulants in adult bipolar depression". Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000326. hdl:2434/265768. PMID 22717304.

- ^ a b Perugi G, Vannucchi G, Bedani F, Favaretto E (January 2017). "Use of Stimulants in Bipolar Disorder". Current Psychiatry Reports. 19 (1): 7. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0758-x. PMID 28144880. S2CID 2932701.

- ^ Shen YC (2018). "Treatment of acute bipolar depression". Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 30 (3): 141–147. doi:10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_71_18. PMC 6047324. PMID 30069121.

- ^ a b Nunez NA, Singh B, Romo-Nava F, Joseph B, Veldic M, Cuellar-Barboza A, et al. (March 2020). "Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive modafinil/armodafinil in bipolar depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Bipolar Disorders. 22 (2): 109–120. doi:10.1111/bdi.12859. PMID 31643130.

- ^ Elsayed OH, Ercis M, Pahwa M, Singh B (2022). "Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression: Therapeutic Trends, Challenges and Future Directions". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 18: 2927–2943. doi:10.2147/NDT.S273503. PMC 9767030. PMID 36561896.

- ^ a b "Modafinil in the treatment of selected mental disorders". ProQuest. Archived from the original on February 14, 2024. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Sousa A, Dinis-Oliveira RJ (2020). "Article commentary: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic of the cognitive enhancer modafinil: Relevant clinical and forensic aspects". Substance Abuse. 41 (2): 155–173. doi:10.1080/08897077.2019.1700584. PMID 31951804. S2CID 210709160.

- ^ Vaccarino SR, McInerney SJ, Kennedy SH, Bhat V (2019). "The Potential Procognitive Effects of Modafinil in Major Depressive Disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 80 (6). doi:10.4088/JCP.19r12767. PMID 31599501. S2CID 204028869.

- ^ a b c Bartoli F, Cavaleri D, Bachi B, Moretti F, Riboldi I, Crocamo C, et al. (November 2021). "Repurposed drugs as adjunctive treatments for mania and bipolar depression: A meta-review and critical appraisal of meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 143: 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.018. PMID 34509090. S2CID 237485915.

- ^ Johnson DE, McIntyre RS, Mansur RB, Rosenblat JD (2023). "An update on potential pharmacotherapies for cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 24 (5): 641–654. doi:10.1080/14656566.2023.2194488. PMID 36946229. S2CID 257665446.

- ^ Salvadore G, Quiroz JA, Machado-Vieira R, Henter ID, Manji HK, Zarate CA (November 2010). "The neurobiology of the switch process in bipolar disorder: a review". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (11): 1488–1501. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05259gre. PMC 3000635. PMID 20492846.

- ^ a b Corp SA, Gitlin MJ, Altshuler LL (September 2014). "A review of the use of stimulants and stimulant alternatives in treating bipolar depression and major depressive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 75 (9): 1010–1018. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08851. PMID 25295426.

- ^ Hughes S (February 1991). "Drugged troops could soldier on without sleep". New Scientist. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ a b Van Puyvelde M, Van Cutsem J, Lacroix E, Pattyn N (January 2022). "A State-of-the-Art Review on the Use of Modafinil as a Performance-enhancing Drug in the Context of Military Operationality". Military Medicine. 187 (1–2): 52–64. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab398. PMID 34632515.

- ^ a b Brunyé TT, Brou R, Doty TJ (2020). "A Review of US Army Research Contributing to Cognitive Enhancement in Military Contexts". J Cogn Enhanc. 4 (4): 453–468. doi:10.1007/s41465-020-00167-3. S2CID 256621326.

- ^ Gonzalez J (July 2017). "Go Pills for Black Shoes?". U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. 143 (7/1, 373). Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Caldwell JA, Caldwell JL (July 2005). "Fatigue in military aviation: an overview of US military-approved pharmacological countermeasures". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 76 (7 Suppl): C39–C51. PMID 16018329.

- ^ Sample I, Evans R (July 29, 2004). "MoD bought thousands of stay awake pills in advance of war in Iraq". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ Martin R (November 1, 2003). "It's Wake-Up Time". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ "Air Force Special Operations Command Instruction 48–101" (PDF). November 30, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2018.

(sects. 1.7.4), U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command

- ^ Thirsk R, Kuipers A, Mukai C, Williams D (June 2009). "The space-flight environment: the International Space Station and beyond". CMAJ. 180 (12): 1216–1220. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081125. PMC 2691437. PMID 19487390.

- ^ Cadwalladr C (February 14, 2015). "Students used to take drugs to get high. Now they take them to get higher grades". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Cumming E (November 3, 2009). "The drug does work". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ "Professors are taking the same 'smart drugs' as students to keep up with workloads". The Independent. May 30, 2017. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Talbot M. "Brain Gain". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ "Towards immortality". The Economist. November 16, 2006. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Van Rooyen LR, Gihwala R, Laher AE (May 2021). "Stimulant use among prehospital emergency care personnel in Gauteng Province, South Africa". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 111 (6): 587–590. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i6.15465 (inactive November 1, 2024). PMID 34382572. S2CID 236402826.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Supercharging the brain". The Economist. September 18, 2004. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS (June 2008). "Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1477–1502. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. PMID 17712350. S2CID 13752498.

- ^ Turner DC, Robbins TW, Clark L, Aron AR, Dowson J, Sahakian BJ (January 2003). "Cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology. 165 (3): 260–269. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1250-8. PMID 12417966.

- ^ a b Keating GM, Raffin MJ (2005). "Modafinil: a review of its use in excessive sleepiness associated with obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and shift work sleep disorder". CNS Drugs. 19 (9): 785–803. doi:10.2165/00023210-200519090-00005. PMID 16142993. S2CID 43733424.

- ^ Meulen R, Hall W, Mohammed A (2017). Rethinking Cognitive Enhancement. Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-19-872739-2.

- ^ Battleday RM, Brem AK (November 2015). "Modafinil for cognitive neuroenhancement in healthy non-sleep-deprived subjects: A systematic review". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (11): 1865–1881. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.07.028. PMID 26381811. S2CID 23319688.

- ^ a b Schifano F, Catalani V, Sharif S, Napoletano F, Corkery JM, Arillotta D, et al. (April 2022). "Benefits and Harms of 'Smart Drugs' (Nootropics) in Healthy Individuals". Drugs. 82 (6): 633–647. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01701-7. hdl:2299/25614. PMID 35366192. S2CID 247860331.

- ^ a b c d e Kumar R (2008). "Approved and Investigational Uses of Modafinil". Drugs. 68 (13): 1803–1839. doi:10.2165/00003495-200868130-00003. PMID 18729534. S2CID 38542387.

- ^ Bello NT (2015). "Central Nervous System Stimulants and Drugs That Suppress Appetite". In Ray SD (ed.). A worldwide yearly survey of new data in adverse drug reactions. Side Effects of Drugs Annual. Vol. 37. Elsevier. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1016/bs.seda.2015.08.004. ISBN 978-0-444-63525-9. ISSN 0378-6080.

- ^ "Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin 2008". Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. December 1, 2008. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020.

- ^ "Provigil" (PDF). Medication Guide. Cephalon, Inc. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ "Modafinil". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. PMID 31643597. NCBI NBK548274.

- ^ "Modafinil (marketed as Provigil): Serious Skin Reactions". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2007. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009.

- ^ Li TW (November 6, 2023). "Three men hospitalised after taking modafinil or armodafinil to stay awake; drugs were not prescribed". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Banerjee D, Vitiello MV, Grunstein RR (October 2004). "Pharmacotherapy for excessive daytime sleepiness". Sleep Med Rev. 8 (5): 339–54. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.03.002. PMID 15336235.

- ^ "FDA Provigil Drug Safety Data" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2017.

- ^ Rugino T (June 2007). "A review of modafinil film-coated tablets for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 293–301. PMC 2654790. PMID 19300563.

- ^ a b c d Bassetti CL, Kallweit U, Vignatelli L, Plazzi G, Lecendreux M, Baldin E, et al. (December 2021). "European guideline and expert statements on the management of narcolepsy in adults and children". Journal of Sleep Research. 30 (6): e13387. doi:10.1111/jsr.13387. hdl:11380/1251554. PMID 34173288. S2CID 235648766.

- ^ Billiard M, Lubin S (2015). "Modafinil: Development and Use of the Compound". Sleep Medicine. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 541–544. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2089-1_61. ISBN 978-1-4939-2088-4.

- ^ a b "Modafinil (Provigil): increased risk of congenital malformations if used during pregnancy". GOV.UK. November 16, 2020. Archived from the original on January 13, 2024. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Krystal A, Attarian H (December 2016). "Sleep Medications and Women: a Review of Issues to Consider for Optimizing the Care of Women with Sleep Disorders". Current Sleep Medicine Reports. 2 (4): 218–222. doi:10.1007/s40675-016-0060-1.

- ^ a b Ghaffari N, Robertson PA (February 2021). "Caution in Prescribing Modafinil and Armodafinil to Individuals Who Could Become Pregnant". JAMA Intern Med. 181 (2): 277–278. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4206. PMID 33074296. S2CID 224780160.

- ^ Cesta CE, Engeland A, Karlsson P, Kieler H, Reutfors J, Furu K (2020). "Incidence of Malformations After Early Pregnancy Exposure to Modafinil in Sweden and Norway". JAMA. 324 (9): 895–897. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.9840. PMC 7489822. PMID 32870289.

- ^ a b Miller M, et al. (Hull & East Riding Prescribing Committee). Morgan J (ed.). "Prescribing Framework for Modafinil for Daytime Hypersomnolence and excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinsons" (PDF). Northern Lincolnshire, UK: National Health Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Modafinil for the treatment of adult patients with excessive sleepiness" (PDF). National Health Service, UK. November 10, 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ "The Safety of Stimulant Medication Use in Cardiovascular and Arrhythmia Patients". Archived from the original on January 29, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Modafinil: Annex III Summary of Product Characteristics, Labelling and Package Leaflet" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 29, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Oskooilar N (October 2005). "A case of premature ventricular contractions with modafinil". Am J Psychiatry. 162 (10): 1983–4. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1983-a. PMID 16199853.